“A remarkable aspect of your mental life is that you are rarely stumped … The normal state of your mind is that you have intuitive feelings and opinions about almost everything that comes your way. You like or dislike people long before you know much about them; you trust or distrust strangers without knowing why; you feel that an enterprise is bound to succeed without analysing it.”

Daniel Kahneman, Thinking Fast, Thinking Slow.

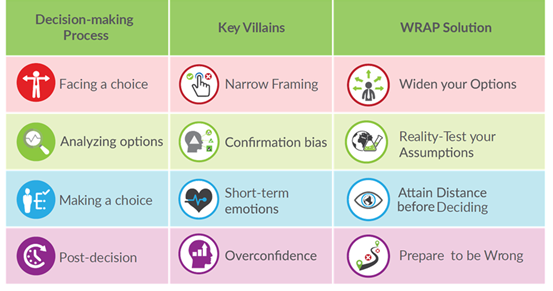

If you think about a normal decision-making process, it usually proceeds in four steps:

- You encounter a choice.

- You analyse your options.

- You make a choice.

- Then you live with it.

In the book Decisive by Heath and Heath (2013) they outline the problem, there’s a villain that afflicts each of these stages:

- You encounter a choice. But narrow framing makes you miss options.

- You analyse your options. But the confirmation bias leads you to gather self-serving information.

- You make a choice. But short-term emotion will often tempt you to make the wrong one.

- Then you live with it. But you’ll often be overconfident about how the future will unfold.

We can’t deactivate our biases, but we can counteract them with the right discipline.

In this discussion we will explore the first villain – narrow framing.

A 1993 study by Paul Nutt, which analysed 168 decisions, found, of the teams he studied, only 29% considered more than one alternative. Heath & Heath (2013) comment, “Nutt found that ‘whether or not’ decisions failed 52% of the time over the long term, versus only 32% of the decisions with two or more alternatives. Why do ‘whether or not’ decisions fail more often? Nutt argues that when a manager pursues a single option, she or he spends most of their time asking: ‘How can I make this work? How can I get my colleagues behind me?’ Meanwhile, other vital questions get neglected such as: ‘Is there a better way? What else could we do?’”

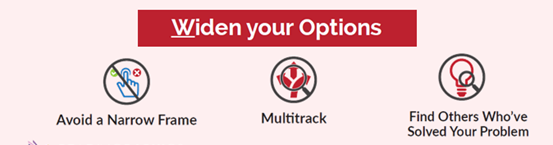

To escape narrow frames, be aware of “whether or not” decisions and employ the skill of “Widening your Options”.

There are a number of ways to widen your options.

1. Explore the Opportunity Cost

Opportunity cost is a term from economics that refers to what we give up when we make a decision. For instance, if you and your spouse spend $40 on a Mexican dinner one Friday night and then go to the movies ($20), your opportunity cost might be a $60 sushi dinner plus some television at home. The sushi-and-TV combo is the next-best thing you could have done with the same amount of time and money.

Adding alternatives improves decision-making. But you won’t brainstorm additional alternatives if you aren’t aware you’re neglecting them. Focusing is great for analysing alternatives but terrible for spotting them. Our lack of attention to opportunity costs is so common that it can be shocking when someone acknowledges them.

Heath et al. (2013) suggest some questions to widen your options. A good quality question to ask is, “What am I giving up by making this choice?” Another technique you can use to break out of a narrow frame is to run the Vanishing Options Test. This involves asking yourself, “You cannot choose any of the current options you’re considering. What else could you do?”

That phrase “either/or” is a classic warning signal that you haven’t explored all your options. When people imagine that they cannot have an option, they are forced to move their mental spotlight elsewhere—really move it—often for the first time in a long while. When you hear the tell tale signs of a narrow frame—people wondering ‘whether or not’ they should make a certain decision or rehashing arguments endlessly about the same limited set of choices—push to widen the options. Another technique is to set an arbitrary number of options that you or your team have to come up with. When coaching leaders who are getting stuck I might ask, “Let’s come up with 10 genuine options to solve this issue.”

2. Create Multi-track Options

Multi-tracking” involves considering several options simultaneously.

Adding one more alternative to your decision will substantially improve your decisions, and it stops well short of triggering decision paralysis.

Decision paralysis is not a big factor in most circumstances—you don’t need a plethora of choices to improve your decisions. You just need one extra choice, or two. The problem is that we often get invested in one or two solutions, now our ego gets involved and we ‘have’ to prove it is the best answer. Multi-tracking reduces the temptation to get stuck on a solution and become stubborn, thus narrow-framing.

To get the benefits of multi-tracking, we need to produce options that are meaningfully distinct. Generating distinct options is even more difficult when our minds settle into certain well-worn grooves. Grooves are triggered when we think about avoiding bad things, and one is triggered when we think about pursuing good things. When we’re in one state, we tend to ignore the other.

There are two forces that unconsciously act to push us towards certain decisions – one is a “moving away from” motivation. We are motivated to avoid a negative consequence, e.g. getting in trouble, bankruptcy etc. The other force is a “moving toward” motivation. We are motivated to pursue or achieve something e.g. a promotion, profits etc.

The wisest decisions may combine the caution of the “moving away” motivation with the enthusiasm of the “moving towards” motivation.

Some of the best exponents of multi-tracking use a list of questions to force people to think about things from various angles. For instance, De Bono’s ^ Hat Thinking is a form of this practice. You can come up with a list of 5 questions that force the group to consider multiple options, from various angles.

3. Find Someone who has Solved Your Problem

Ask yourself, “Who else is struggling with a similar problem, and what can I learn from them?”

To break out of a narrow frame, we need options, and one of the most basic ways to generate new options is to find someone else who’s solved your problem. Sometimes the people who have solved our problems are our own colleagues. Sometimes they are competitors, and sometimes they are people from very distinct disciplines.

The interesting thing that this technique does is help to challenge your assumptions and biases. For instance, if you are a not-for-profit and you are struggling to raise enough money you could be telling yourself that there isn’t money available at the moment or people aren’t generous or the state of the economy is at fault. This creates a narrow-framing and confirmation bias.

However, if you look for others in that industry who are raising more than enough money suddenly those assumption are challenged, your narrow frame widens and you can study what they are doing differently and better than you.

Widening the options takes effort.

It takes effort because we are unaware that we are thinking narrowly – either/or and that our biases are blinding us to what we aren’t considering.